The crisis of the migrant workers in India

Suddenly, India seems to have woken up

to the plight of its internal migrants who work in the unorganized labor

sectors. It had occurred to no journalist or social media activist,

politicians in opposition or those in power, state governments or the

central government that an immediate nationwide lockdown would end up

stranding Bihari service providers working in Delhi, Bengali carpenters

and electricians working in Kerala, Chhattisgarhi brick kiln workers

working in Uttar Pradesh or roadside vendors in Delhi whose hometowns

are in Rajasthan. We did not read social media posts or read tweets from

these hundreds and thousands of people because they do not have access

to social media, it does not occur to them that what has been done to

them is wrong and they have a right to protest and demand for

repatriation services. While the rest of the nation was ‘staying home,

staying safe’, these workers were, in effect told, ‘stay on the streets,

you are on your own’.

Whose job is it to think of migrant workers, who migrate from their home states to other states for work? Whose responsibility should it have been to organize transport for them to have returned home with safety and precautions to prevent transmission? Is it the state government’s responsibility, or the Centre? Is it the responsibility of the sending state – where these migrants’ homes are, or the responsibility of the receiving state – where they work? Who should have taken the initiative to mobilize the workers, organize them, prepared for logistics and helped them return?

The obvious response may be the Labor department and Ministry. Labor is a concurrent subject in our country, where the central government and the state governments both have jurisdiction to legislate and act. India has an existing legislation The Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, which has been one of the most poorly implemented legislations in the country. While the legislation has some good provisions on how the labor departments of each state can monitor and ensure protection from abuse and exploitation of migrants who are recruited, transported and supplied to employers in the unorganized labor sectors, the provisions have gone unimplemented for nearly 4 decades, resulting in lack of protection and safety of most vulnerable migrants in India.

India’s labor laws have often been criticized as being too complex, archaic and inflexible. The Central Government introduced a new bill called the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions in 2018 which aimed to subsume 14 of the existing labor laws into a single legislation, including the Interstate Migrant Workmen Act, 1979. The 2018 bill lapsed because of the national elections and was subsequently been re-introduced in the Lok Sabha on 23rd July, 2019 and after strong criticism from the opposition, the Ministry agreed to send the bill to the Parliamentary Standing Committee, headed by Bhartruhari Mahtab, for review. The Committee found that the bill is inadequate in its coverage of issues of interstate migrant workers, an observation confirmed by several state governments who were consulted by the Committee. One of the glaring gaps, for example, is – in its chapter on Safety, the lack of consideration of how migrant workers will be protected in the event of emergency or a calamity, how they would be supported in repatriation to their homes, or what the employers’ responsibility would be. The Committee challenges the exclusion of contract workers of the center and state governments and proposes to include all unorganized workforce under the purview of the code, which would mean extending the code to an estimated 50 crore unorganized workers including railway porters, construction workers and security guards, who do not come under the membership or purview of most trade unions. Trade Unions, which only work in the organized sectors account for only 8 crore workers. It also recommended streamlining and expanding government’s labor department to reach out to the unorganized sectors and bring such workers under the code purview.

Migrant workers from the unorganized sectors in India have no information or involvement in the making of this law, their exclusion from it. The India-Lockdown crisis has amplified the need for the Ministry of Labor and Employment to necessarily write a separate chapter for interstate migrant workers and include all workers from the unorganized sectors. The legislation needs to clearly lay down responsibility and accountability measures of state labor departments in jointly creating coordination systems that could respond to situations of crisis such as COVID 19. Interstate migrant workers are a group of most vulnerable workers in the country, where they end up feeling like in a no man’s land – in a situation of crisis, neither does the host state where they work think of them as their own people, and because they are far away from their home state, they are out of sight and out of mind even for an otherwise proactive state government. They are most vulnerable to not only overnight loss of income, but also homelessness, with no food or travel facility rendering young children and the old, to starvation and destitution.

Whose job is it to think of migrant workers, who migrate from their home states to other states for work? Whose responsibility should it have been to organize transport for them to have returned home with safety and precautions to prevent transmission? Is it the state government’s responsibility, or the Centre? Is it the responsibility of the sending state – where these migrants’ homes are, or the responsibility of the receiving state – where they work? Who should have taken the initiative to mobilize the workers, organize them, prepared for logistics and helped them return?

The obvious response may be the Labor department and Ministry. Labor is a concurrent subject in our country, where the central government and the state governments both have jurisdiction to legislate and act. India has an existing legislation The Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, which has been one of the most poorly implemented legislations in the country. While the legislation has some good provisions on how the labor departments of each state can monitor and ensure protection from abuse and exploitation of migrants who are recruited, transported and supplied to employers in the unorganized labor sectors, the provisions have gone unimplemented for nearly 4 decades, resulting in lack of protection and safety of most vulnerable migrants in India.

India’s labor laws have often been criticized as being too complex, archaic and inflexible. The Central Government introduced a new bill called the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions in 2018 which aimed to subsume 14 of the existing labor laws into a single legislation, including the Interstate Migrant Workmen Act, 1979. The 2018 bill lapsed because of the national elections and was subsequently been re-introduced in the Lok Sabha on 23rd July, 2019 and after strong criticism from the opposition, the Ministry agreed to send the bill to the Parliamentary Standing Committee, headed by Bhartruhari Mahtab, for review. The Committee found that the bill is inadequate in its coverage of issues of interstate migrant workers, an observation confirmed by several state governments who were consulted by the Committee. One of the glaring gaps, for example, is – in its chapter on Safety, the lack of consideration of how migrant workers will be protected in the event of emergency or a calamity, how they would be supported in repatriation to their homes, or what the employers’ responsibility would be. The Committee challenges the exclusion of contract workers of the center and state governments and proposes to include all unorganized workforce under the purview of the code, which would mean extending the code to an estimated 50 crore unorganized workers including railway porters, construction workers and security guards, who do not come under the membership or purview of most trade unions. Trade Unions, which only work in the organized sectors account for only 8 crore workers. It also recommended streamlining and expanding government’s labor department to reach out to the unorganized sectors and bring such workers under the code purview.

Migrant workers from the unorganized sectors in India have no information or involvement in the making of this law, their exclusion from it. The India-Lockdown crisis has amplified the need for the Ministry of Labor and Employment to necessarily write a separate chapter for interstate migrant workers and include all workers from the unorganized sectors. The legislation needs to clearly lay down responsibility and accountability measures of state labor departments in jointly creating coordination systems that could respond to situations of crisis such as COVID 19. Interstate migrant workers are a group of most vulnerable workers in the country, where they end up feeling like in a no man’s land – in a situation of crisis, neither does the host state where they work think of them as their own people, and because they are far away from their home state, they are out of sight and out of mind even for an otherwise proactive state government. They are most vulnerable to not only overnight loss of income, but also homelessness, with no food or travel facility rendering young children and the old, to starvation and destitution.

DISCLAIMER : Views expressed above are the author's own.

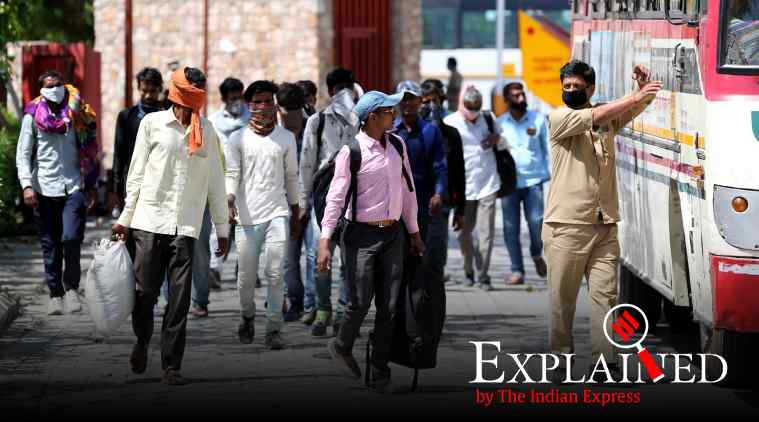

Migrants who comes from different part of India being shifted to their

native place from Shelter home after note their names and addresses at

Awadh Shilp Gram in Lucknow (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Migrants who comes from different part of India being shifted to their

native place from Shelter home after note their names and addresses at

Awadh Shilp Gram in Lucknow (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav) Tariq Thachil

Tariq Thachil Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves.

Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves. Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged.

Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged. Migrant workers returning to their homes in UP sleep at a shelter home in Lucknow.

Migrant workers returning to their homes in UP sleep at a shelter home in Lucknow. Migrants queue at Peetol checkpost on NH48 in Gujarat’s Dahod district, on the state’s border with Madhya Pradesh.

Migrants queue at Peetol checkpost on NH48 in Gujarat’s Dahod district, on the state’s border with Madhya Pradesh. Migrants sitting atop a bus as they leave from Lucknow.

Migrants sitting atop a bus as they leave from Lucknow.