After The Coromandel Train Wreck: Unemployed, Young Migrant Workers Struggling With Health Costs & Lost Wages

From speaking to passengers who survived the 2 June 2023 Balasore train accident in Odisha, a picture emerges of India’s migrant labourers: Many are young, often school dropouts, who travelled long distances to find menial jobs because there was no work at home, on farms or otherwise. Without medical insurance and paid leave, they struggle now with health costs and lost wages.

Mumbai: More than two weeks since he alighted from a derailed coach of the Shalimar-Chennai Coromandel Express train and walked, dazed and terrified, to a nearby school in the village of Bahanaga in northern Odisha, Osman Shaikh, 27, said he couldn’t summon the courage to make a fresh reservation.

“But I’ll have to board the very same train eventually,” he said, “because I need to resume earning a living.”

A semi-skilled worker from West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district, Osman Shaikh was preparing to eat a small pre-packed meal with younger brother Ajijul, 17, in a sleeper class coach not far behind the ‘general’ coach for unreserved passengers when their speeding train smashed into a stationary goods train just after it had crossed Balasore station in northern Odisha.

Their coach was wrecked, as derailed coaches hit a passenger train on a parallel track, causing some bogies of the latter train to derail too. The 2 June 2023 tragedy was one of the Indian Railways’ worst ever, killing 290 people and injuring at least 1,000.

“It’s surprising that more people didn’t die,” Osman Shaikh told Article 14 over the phone from his home in Bhaidarpara village near Purbasthali railway station, about 130 km north of Kolkata. He said he saw at least 120 bodies just hours after the accident, at the Bahanaga school that was turned into a temporary morgue.

A rajmistry (mason) who has worked at construction sites in Kerala’s Malappuram district for nearly a decade, always taking the Coromandel Express to Chennai and another train to Tirur in Malappuram, he said there would have been about 400 people packed into the unreserved coach, almost all of them migrant labourers from the eastern states of Bihar, West Bengal and Odisha, heading to Chennai, other parts of Tamil Nadu and Kerala in the south.

This was the most inexpensive way for labourers to travel, squatting in passages and pressed against scores of others for most of the 27-hour train journey, he said.

The “general dabba” or unreserved coach of the Coromandel Express was, in recent years, a pipeline of men looking for work in southern India, bolstering one of the country’s several well-established migration corridors for informal labour. Older migration corridors for unorganised workers, many similarly served by the Indian Railways, run from various districts of Uttar Pradesh to Mumbai; south Rajasthan to Pune/Mumbai; Ganjam in coastal Odisha to power looms in Surat, Gujarat; from Marathwada in central Maharashtra for the sugarcane harvest to western Maharashtra and Bagalkot in Karnataka; and from north Bihar’s flood-prone areas near the Kosi river to farms in Punjab.

What drives millions of young Indians to these migration corridors is the search for sustainable employment, evidenced by, among other things, the continuing pressure on the farm sector—from 42.5% as per the 2018-19 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of the ministry of statistics & programme implementation, agriculture employed 46.5% of the total workforce in 2020-21, dipping marginally to 45.5%, in 2021-22.

As per the PLFS, in the year 2017-18, the total employment in both organised and unorganised sectors was around 470 million. Of this, 380 million were unorganised workers, more than 81% of total employment in the country. By some estimates, 194 million workers are migrants, in addition to 15 million short-term or circulatory migrants.

Already, the union ministry of labour and employment has registered 289.3 million unorganised workers, only a little short of USA’s population of 331 million, on its e-Shram website, a database of construction workers, migrant workers, gig workers, street vendors, domestic workers, agricultural labourers, etc.

Despite their large numbers, however, migrant workers were never offered social, economic, or health protection at their places of work until the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted their plight.

‘Better Than At Home’

The ride on the Coromandel Express was to have been Ajijul Shaikh’s first trip to Kerala—a fresh school dropout after failing his Class X exams, he was to earn Rs 15,000 per month as a helper and cook for a group of migrant labourers living together.

“We

work 12-hour days at construction sites, often in the heat,” said Osman

Shaikh, whose head and leg were injured from being flung against the

wall of the coach upon impact.

At wages of Rs 800 to Rs 1,200 per day in Kerala and up to Rs 1,000 per day in Tamil Nadu depending on their skill levels, tens of thousands from Purba Bardhaman and other districts of West Bengal and Odisha make the long journey and endure the hardscrabble life of migrant labourers for the opportunities it presents.

From the accounts of nearly a dozen passengers in the unreserved and non air-conditioned sleeper coaches of the ill-fated Coromandel Express, a picture emerged of this large segment of India's informal workforce: Those with minor to moderate injuries lamented the cost of medical care, not having health coverage from the state or their employers. Those advised diagnostic scans paid Rs 6,000 to Rs 8,000 for these, for many nearly a third of their monthly income. Each of them forfeited weeks of income in the absence of any kind of paid leave.

Almost all the men were less than 35 years old. Most were school dropouts, having quit school to earn, then being forced to work in menial jobs for want of educational and professional qualifications. All of them boarded the train due to unemployment or underemployment in their home state, some additionally burdened by the loss of farm income.

Menial jobs were still “better than at home”, said Osman Shaikh.

When their mud house collapsed in a flood a few years ago, he took loans, from a bank and from money-lenders, to build a pucca house. “We are able to repay it only because I am working in Kerala,” he told Article 14. “There is no question of not going back.”

About two decades ago, their farmland began to flood in the monsoon swell of the Khari river flowing eastward into the Bhagirathi-Hooghly. That is when Osman Shaikh’s father ventured out of the state, as far as Bengaluru, to find work. “Now every district of Kerala is full of Bengali workers,” he said.

Medical Expenses, Lost Wages Add Up

Osman Shaikh spent Rs 10,000 on a medical check-up, blood tests and scans at a private clinic in Kalna, a town located 25 km from his village. Until the scans were completed, he was advised to get admitted to the clinic.

Shatrughan Sika, 39, of Mohar village in Paschim Medinipur district in south western West Bengal has worked for seven years at an iron and steel factory near Tambaram, a Chennai suburb with an exports processing zone. With a strained back from the derailment, Sika decided to return to work anyway.

Two weeks without wages and

the unexpected additional journey home from the accident site—a bus to

Balasore, a train to Midnapore and another bus ride to his village— had

already set back the family’s finances. “I’ll take any ticket that’s

available,” he said. “It’s time to go back to work.”

Neither Osman Shaikh nor Sika had medical insurance or paid leave.

Salim Shaikh, 26, also a mason, from Purba Bardhaman’s Bamsor village, was travelling with his brother Rahim in a group of eight youngsters from the same village, who eventually hired a private vehicle to return to Bardhaman from the accident site in Bahanaga.

Salim Shaikh of Purba Bardhaman district in West Bengal takes a selfie with his brother and friends before boarding the Coromandel Express at Shalimar station on 2 June. They were all headed to Kerala, to work in Malappuram and Vadakara./ SALIM SHAIKH

A shoulder injury from the derailment has left him house-bound for the next two months, but the village was abuzz with excitement in the week after the incident when Bardhaman-Durgapur member of parliament S S Ahluwalia of the Bharatiya Janata Party visited all eight young men.

“He gave me Rs 10,000, to help with expenses,” Salim Shaikh told Article 14. Having returned home on a short trip for a cousin’s wedding, he has now already been without work for more than a month.

“I can’t walk, I can’t stand up properly,” he said over the phone. He, too, paid for a full body scan, and then handed over his medical documents to a political party worker in the hope of seeking the government-announced compensation for injured passengers. His brother sustained injuries to the head.

There is no year-round work available in Bamsor or even in Bardhaman town, he said.

Belonging

to a family of landless labourers, their father used to work on

government road construction sites in the state. Three years ago, having

dropped out after high school, Salim Shaikh got in touch with a labour

contractor who regularly hired labourers from Paschim Bardhaman for work

in Malappuram district and in Vadakara, in coastal Kerala.

All of 18 then, he started as a labourer carrying mud and digging pits, before learning masonry and painting.

The School Children On The Coromandel Express

It was getting dark when the Coromandel Express slid off its tracks after ramming a stationary freight train on the night of 2 June. As Coach S4 collapsed on its side, passengers began to cry for help, most of them thrown to the floor in a heap.

One group of children, 11 to 16 years old, all from Araria in northeastern Bihar and travelling to Kerala, climbed slowly out of the wreckage through a mangled window. The other members of their group joined them and their two adult chaperones shortly afterwards, from the other coaches. In all, there were 20 children including 12 girls.

“They

spent the night at a stranger’s house by the tracks,” said Mohammed

Kasim, also from Araria and the brother of one of the boys, over the

phone. The next morning, government officials assisted the group to

return to Bihar. “They attend school in Kerala,” said Kasim, who has

also worked in Kerala as a labourer.

The students had taken a train from Araria to Shalimar in West Bengal, then boarded the Coromandel Express to Chennai, from where they were to take a third train to Kerala, nearly 2,500 km from home.

Tasnim Arif, a social activist from Darbhanga in Bihar who has worked on issues of gender and education in the Seemanchal region on the border with West Bengal, said scores of students from impoverished Muslim families in this region attended boarding schools in Kerala.

Arif said educational institutions including madrasas in Kerala offered students from Bihar, particularly the Seemanchal districts of Araria, Kishanganj, Purnea and Katihar, attractive enrolment benefits, including free education and boarding schools. “This is in addition to quality education, particularly in Arabic and English, which are lacking in local madrasas,” said Arif.

Seemanchal, a socio-economically backward region, has an average of 47% Muslims in each district, against Bihar’s statewide average of 17%.

“For

the very poor Muslim families here, Kerala is like the Gulf,” continued

Arif, who himself completed his master’s in social work from the

University of Calicut, Kerala, inspired by the Anna Hazare movement of

2013.

Thousands of workers from Seemanchal travel to Kerala to look for work too, he said. “And when they return, they’re able to do the things they couldn’t otherwise, such as build a home or arrange a sister’s wedding, or buy an asset.” According to Arif, better health and sanitation facilities for labourers in Kerala, coupled with the better wage rates, made it an ideal destination for migrant workers.

The Lure Of The South

Activists said Odiya and Bengali workers were now very common in Kerala, among naka workers and construction workers. The dihadi, or the daily wage rate, hovering in the region of Rs 400 a day in Bengaluru, is Rs 800 a day in Kerala. Some said workers also preferred Kerala on account of lower discrimination against outsiders.

Long-time labour rights activist Chandan Kumar of the Working People’s Coalition, a collective of labour unions, said that in 2013-14, he and a group of activists had found out through an application under the Right To Information Act, 2005 that the little station of Kantabanji in Odisha, which frequently witnessed only 25 to 30 passengers on a daily basis, sold lakhs of tickets in the months after the completion of the state’s Nuakhai agricultural festival, around September.

“The station of Kantabanji is located strategically and is accessible to workers from Nuapada, Rayagada, Bolangir and Kalahandi,” Kumar said. “The data of the passengers on those trains going south from Kantabanji was a testament to labour distress and migration.”

Just as in those years the Railways could have added coaches to trains in the months when migration peaked, data and enumeration can make a huge change in providing social security to migrant workers across the country, he said.

The e-Shram exercise of

creating a database of unorganised workers is incomplete, he added. The

schemes being offered such as a pension plan are contributory in

nature, and the central government should instead run an anchor social

security scheme for registered workers, Kumar said.

Launched in August 2021, the promised benefits of e-Shram included efficient implementation of social security services, portability of social security and welfare schemes, and a comprehensive database that would be handy in times of crisis. In April 2023, the union government introduced additional features to capture workers’ family details. Among the services available for e-Shram registered workers are skilling, apprenticeship, a pension scheme and connectivity to states’ schemes.

However, as Article 14 reported, workers’ experience with e-Shram has been marked by difficulties in linking their original Aadhaar-linked phone numbers, technical and language barriers leading to over-reliance on the common service centres (CSCs) and confusion in the absence of clearly defined social security measures to be rolled out to this database of workers.

“E-Shram was meant to give portability for entitlements,” said Kumar. “The government now has bank details, Aadhaar details of workers. They can easily enrol these workers in social security programmes.”

Additionally, social security programmes run by state governments are often not accessible to outsiders, whether it is through the requirement of a domicile certificate to avail a free bus ride for women workers or accident insurance schemes denied to workers from outside the state. These were anti-migrant policies couched in nativist politics, according to Kumar.

In a study sponsored by the National Human Rights Commission in October 2020, the Kerala Development Society, a non-profit, found that 65% of interstate migrant workers surveyed in Gujarat, 61% in Haryana and 69% in Maharashtra reported non-provisioning of entitlements as per government schemes; while 51.2% in Delhi, 53% in Gujarat, 56% in Haryana and 55% in Maharashtra had poor access to available schemes due to language barriers and the lack of information.

For Families, The Tragedy Continues

Soft-spoken and still hopeful then, Shaikh Zakir Hussain from 24 South Parganas in West Bengal was interviewed on 3 June by journalist Tamal Saha.

He was in Bahanaga, at the school turned into a morgue, searching for his nephew and brother who were missing, Meraj Shaikh and Abdul Majid Shaikh. Trained masons, they were headed to Chennai.

On his way to Bahanaga, Hussain met Noorul Huda Shaikh of Kakdwip, also in 24 South Parganas, who was looking for his brothers Shamshul and Asmaul, also migrant labourers going to Chennai. Together, the men spent hours searching the site of the accident, the ambulances and other vehicles coming to the school, then repeatedly checked all the bodies lined up on the floor in a hall.

By 6 June, Hussain was alone, but still searching. Around 8.30 pm, he was outside the Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences in Bhubaneswar, his phone nearly discharged, waiting to be let into the morgue. On 7 June, he was asked to give samples for a DNA test—he could not identify his relatives among the dead, nor were they in the hospitals.

On 5 June, he had also been to a business park in Balasore “where bodies were kept on ice”, alongside passengers’ belongings from the train wreckage.

After giving samples for a DNA test, Hussain retraced his steps to check once again at the earlier locations, and found Meraj’s body at the Bahanaga school.

“I spent eight days there,

and only the last two nights I got shelter in a government office. I had

no food and no place to sleep,” Hussain told Article 14. He had

returned home with one body, that of his nephew, in his late 20s,

married less than a year ago. “His wife is pregnant with their first

child,” he said sadly. “Not finding my brother’s body is equally

terrible.”

On 17 June, there were still 81 unclaimed bodies in Bhubaneswar.

On 18 June, the toll rose to 292, two weeks after union minister for railways Ashwini Vaishnaw reportedly said rescue operations were complete and the final number of casualties was 233. West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee had said the death count could rise.

DNA tests on relatives claiming bodies should have been done from the start, Hussain said, to prevent bodies being mis-identified, particularly in the rush to claim the government compensation cheque. His brother had never left the state to look for work earlier, and was accompanying his nephew for the first time, pushed by adverse financial circumstances. The men were travelling in the general coach.

“The money I have spent just going to all these places during these days,” Hussain said, “will be a waste if I eventually don’t find my brother.”

For First Generation Migrants, A Chance At A New Life

At 18, Ashish Bain of Murshidabad in West Bengal uses the data services on his mobile phone to watch YouTube videos, download Bollywood songs to replace his caller tune, and update his social media status.

Having cleared his class 10 board exams a little over a year ago, he decided that higher education was not for him, and decided to pick up a skill instead. For six months, he worked in Kolkata, 200 km south of his home, as an apprentice at a carpentry unit.

“Then I heard from friends who had gone from Murshidabad to Kerala that there is more money to be made there,” he said. Having worked at a large-scale furniture manufacturing unit in Calicut, Kerala for the last nine to 10 months, he visited his hometown for a wedding in May and was returning to Kerala with two prospective co-workers on 2 June.

“I make Rs 20,000-Rs 25,000 in a good month,” Bain said.

His

income depends on the size of contracts his employer bags from large

furniture stores that retail cabins, beds, almirahs and tables,

requiring supplies in bulk. The furniture is mostly made of acacia wood,

with many hand-crafted parts.

“Here in the village, I would not be able to earn even Rs 5,000 a month.” Not even in Kolkata could one earn Rs 20,000 a month, said Bain.

In Murshidabad, the only work easily available is on the farm, and that is seasonal labour. “If I work for one month, there will be no work for the next two months,” he said, about paddy cultivation in the region. His grandfather and father were both farmers, and Bain was the first in the family to explore work avenues outside the state.

The 18-year-old sends his savings home by bank transfer each month. It was a simple life in Calicut, but not as frugal as in the village. For a shared living space that costs Rs 1,500 in rent, and for food and entertainment expenses, he sets aside Rs 9,000 a month.

A minor leg injury from the accident has already healed, Bain said. “I’m ready to set off again.”

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14 and the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss’, a book on India’s farm crisis.)

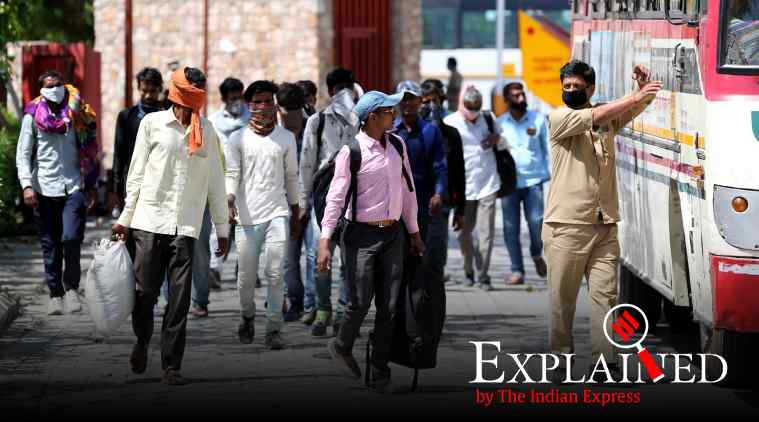

Migrants who comes from different part of India being shifted to their

native place from Shelter home after note their names and addresses at

Awadh Shilp Gram in Lucknow (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Migrants who comes from different part of India being shifted to their

native place from Shelter home after note their names and addresses at

Awadh Shilp Gram in Lucknow (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav) Tariq Thachil

Tariq Thachil Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves.

Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves. Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged.

Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged. Migrant workers returning to their homes in UP sleep at a shelter home in Lucknow.

Migrant workers returning to their homes in UP sleep at a shelter home in Lucknow. Migrants queue at Peetol checkpost on NH48 in Gujarat’s Dahod district, on the state’s border with Madhya Pradesh.

Migrants queue at Peetol checkpost on NH48 in Gujarat’s Dahod district, on the state’s border with Madhya Pradesh. Migrants sitting atop a bus as they leave from Lucknow.

Migrants sitting atop a bus as they leave from Lucknow.