An Expert Explains: ‘A silver lining of the lockdown will be highlighting the essential role migrants play in functioning of Indian cities’

Tariq Thachil's surveys found most migrant workers live in cramped rented rooms or sleep on the footpath, lack documents to access benefits such as rations in the city, do not have family members in the city, and have few savings to draw upon.

Written by Sushant Singh

|

Updated: April 2, 2020 11:10:50 pm

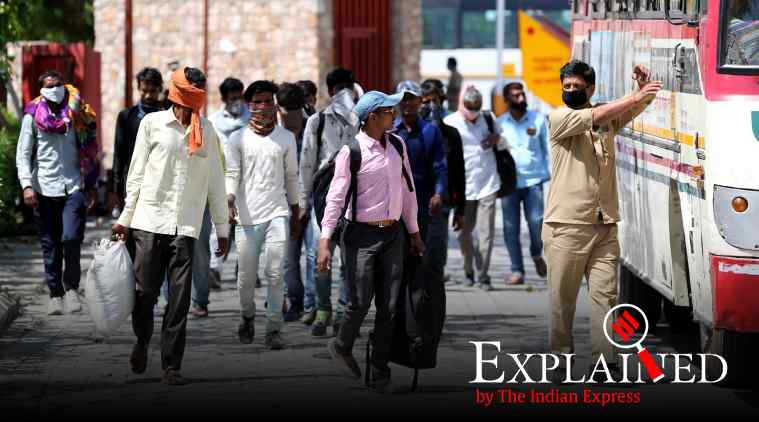

Migrants who comes from different part of India being shifted to their

native place from Shelter home after note their names and addresses at

Awadh Shilp Gram in Lucknow (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Tariq Thachil is an Associate Professor in the Department of

Political Science at Vanderbilt University. His current research focuses

on understanding the political consequences of rapid urbanisation and

internal migration in India. He spoke to The Indian Express about internal and circular migrant labour in India.

Migrants who comes from different part of India being shifted to their

native place from Shelter home after note their names and addresses at

Awadh Shilp Gram in Lucknow (Express photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Tariq Thachil is an Associate Professor in the Department of

Political Science at Vanderbilt University. His current research focuses

on understanding the political consequences of rapid urbanisation and

internal migration in India. He spoke to The Indian Express about internal and circular migrant labour in India.What is unique about the migrant labour in urban areas of India, compared to other countries and societies?

Tariq Thachil

Tariq Thachil

Migrant labour in Indian cities, and the

vast majority of workers currently in the news, are marked by three

traits: internal migration, informality, and circularity. First, these

migrants come from within India, unlike international migrants who often

dominate the study of migration. Second, they are low-income workers

who are informally employed, meaning they lack formal contracts. Many

migrant workers perform daily wage labor (such as beldars on

construction sites), or are self-employed (for example street vendors).

Such employment is obviously precarious and day-to-day in nature, with

no protections in the event of an abrupt cancellation, as has happened

with the lockdown. Third, most of these migrants do not permanently

relocate to the city. Expensive and inhospitable urban environments

compel them to move without their families. Instead, they circulate

between city and village several times a year, and remain deeply rooted

within sending villages. Each of these factors is important in

understanding why migrant workers have been so eager to return home

since the lockdown was announced.

This circular and informal labour is contrasted with the more

permanent and formal labor that characterized the urbanizing transition

from farm to factory in wealthier economies during the Industrial

Revolution. However, it would be wrong to say circular migration is

unique to India. Internal migrants outnumber international migrants by a

three to one ratio, and many internal migrants observe circular

migration and are informally employed. Informal circular migrants are

important populations in countries ranging from Bangladesh to

Mozambique. What makes India’s migrant crisis unique is not the nature

of its migrant workforce but the abruptness of its public policy.What is their contribution to the Indian economy? Has it been recorded and acknowledged properly and accurately?

Quite simply, no, for two reasons. First, the informal nature of employment makes it hard to collect reliable data even on the size of this population, let alone its economic contributions. That said, we can gain a sense of these contributions by considering sectors in which employment is dominated by circular migrants. More fine-grained studies have revealed circular migrants are influential, and in some cases, the predominant forms of labor in industries ranging from construction, brick manufacturing, mining and quarrying, hotels and restaurants, and street vending. Many of these sectors are integral to the Indian economy, and comprise a significant share of our national GDP. Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves.

Beyond official statistics however, there is a broad societal

reluctance to acknowledge the contributions of circular migrants.

Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves. Yet too

often this work is not received with gratitude by municipal authorities

or more privileged urbanites. The migrants I have spoken to repeatedly

offer examples of their harassment and mistreatment by urban employers,

middle-class shopkeepers and residents, and local police. Perhaps one

silver lining of the lockdown will be that the exodus of migrants

renders visible the essential role they play in the functioning of

Indian cities.

Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves.

Beyond official statistics however, there is a broad societal

reluctance to acknowledge the contributions of circular migrants.

Circular urban migrants perform essential labour and provide services

that many people want but are unwilling to provide themselves. Yet too

often this work is not received with gratitude by municipal authorities

or more privileged urbanites. The migrants I have spoken to repeatedly

offer examples of their harassment and mistreatment by urban employers,

middle-class shopkeepers and residents, and local police. Perhaps one

silver lining of the lockdown will be that the exodus of migrants

renders visible the essential role they play in the functioning of

Indian cities.What are your estimates about the number of migrant labourers in urban India? What is their general socio-economic and educational status?

This is a simple question with a complicated answer. Unfortunately, we lack a consensus estimate of the size of our circular migrant population for a number of reasons. Many official data sources use definitions of migration that fail to capture the transient and itinerant patterns observed by circular migrants. For example, India’s landmark National Sample Survey (NSS) collected specific data on migration in its 64th round, and found the all-India rate of ‘short-term migration’ is between 1 and 2 percent. This rate would roughly suggest a population of between 13 and 26 million short-term migrants. Yet the figure is likely to be a dramatic underestimate.The NSS defines a ‘short-term’ migrant as one who stays away for up to 6 months during the last year, but many circular migrants spend most of the year working in cities, returning home for festivals, harvests, or to see family. Further, the fact that these migrants live and work in informal conditions in cities, and circulate between village and city, makes them especially difficult to access through standard residence-based surveys.

Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged.

Alternative data sources suggest India’s circular migrant population

is substantial. According to the national census of 2011, more than half

of all rural residents live off the earnings they make through

unskilled labor, many of whom are likely to do so in cities. Some

scholars have drawn on employment figures from migrant-dominated sectors

like construction to estimate the number of circular migrants is nearly

120 million. The truth may lie in the middle, but either way we are

talking about tens of millions of people.

Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged.

Alternative data sources suggest India’s circular migrant population

is substantial. According to the national census of 2011, more than half

of all rural residents live off the earnings they make through

unskilled labor, many of whom are likely to do so in cities. Some

scholars have drawn on employment figures from migrant-dominated sectors

like construction to estimate the number of circular migrants is nearly

120 million. The truth may lie in the middle, but either way we are

talking about tens of millions of people.There is greater consensus on the average economic status of circular migrants. Most studies agree the vast majority of circular migrants are economically disadvantaged. My own surveys of circular migrants aligned with this consensus. I surveyed 3,018 circular migrants working as daily wage laborers and 1,200 migrants working as street vendors across Delhi and Lucknow. One important finding from this survey was that circular migrants were uniformly poor, but diverse in caste and faith. 27 per cent were from Scheduled Castes, 44 per cent from the Other Backward Classes, 18 per cent from the upper castes, and 12 per cent were Muslims. Yet the average income of migrants within each of these social groups was practically identical—and 75 per cent earned less than $2 per day. Also, 77 per cent had no secondary education, and 74 per cent had no household electric connection in their home villages. Over half of them had ongoing debts they had to pay off. Such homogeneity across caste and religious divisions sharply contrasts with rural sending communities, where economic well-being varies sharply across caste and religious groups.

Were you surprised by the mass exodus of migrant labour after the lockdown was announced by the government? Could it have been prevented?

The exodus of migrant workers is far from surprising. In this respect, I disagree with the Supreme Court’s recent observation that the exodus was caused by irrational panic triggered by misinformation. Unless they have some concrete data to back this claim that I am not privy to, the exodus is best viewed as a highly rational response. Any ‘surprise’ from observers is due to our own lack of information regarding these communities. Specifically, observers are unaware of how rooted circular migrants are in their sending villages, as well as how inhospitable the conditions are under which they must live and work in their destination cities. My own surveys found most migrant workers live in cramped rented rooms or must sleep on the footpath, lack documents to access benefits such as rations in the city, do not have family members in the city, and have few savings to draw upon. They also face considerable harassment from police and middle-class elites, who view them as unclean, nuisances, or criminal. The lockdown takes away their only reason for enduring such hardships: work in the city. Moreover, given the nature of the novel coronavirus, it would be completely plausible for migrants to be unsure about when work opportunities might actually resume in cities. Why then would they stay in harsh conditions away from their families? Migrant workers returning to their homes in UP sleep at a shelter home in Lucknow.

A more effective and humane response would have first considered how

an abrupt lockdown might affect transient populations. Given the

lockdown order required everyone to stay at home for a prolonged period,

it is especially important to consider those populations who are often

forced to work far away from their homes. Second, a more effective

response would have decided whether to prioritize keeping migrants in

place in destination cities, or helping them safely reach home.

Currently the policies enacted by governments at various levels are

swinging back and forth between these two strategies, preventing the

chance of either being successful. If the goal was to get migrants

safely home, resources should be targeted to ensure safe and clean

passage, and a feasible local quarantine strategy for migrants in their

home regions. If the goal was to keep them in the city, resources should

target keeping them healthy, housed, and fed (including by enabling

them to pay our pause rent, and access PDS benefits in cities).

Migrant workers returning to their homes in UP sleep at a shelter home in Lucknow.

A more effective and humane response would have first considered how

an abrupt lockdown might affect transient populations. Given the

lockdown order required everyone to stay at home for a prolonged period,

it is especially important to consider those populations who are often

forced to work far away from their homes. Second, a more effective

response would have decided whether to prioritize keeping migrants in

place in destination cities, or helping them safely reach home.

Currently the policies enacted by governments at various levels are

swinging back and forth between these two strategies, preventing the

chance of either being successful. If the goal was to get migrants

safely home, resources should be targeted to ensure safe and clean

passage, and a feasible local quarantine strategy for migrants in their

home regions. If the goal was to keep them in the city, resources should

target keeping them healthy, housed, and fed (including by enabling

them to pay our pause rent, and access PDS benefits in cities).What is the response of the villages when these migrant labour go back? Are they welcome there usually, leave alone in a health crisis?

In my own travels with migrants back to sending villages, I found the typical reception to be warm within their families. Of course, there are always variations in experience. One migrant I grew close with complained his family treated him ‘like an ATM’ when he returned, only interested in the cash he brought home. More serious variations were underpinned by caste and class hierarchies in the village. For example, Dalit migrants I spoke to complained of harassment from upper castes in their village, especially if they returned with any sign of newfound prosperity (new clothes, or gifts for family). Migrants queue at Peetol checkpost on NH48 in Gujarat’s Dahod district, on the state’s border with Madhya Pradesh.

Clearly the pandemic

has produced certain specific responses, such as disturbing images of

migrants being rounded up and sprayed with harmful chemicals. Yet these

responses are hardly divorced from longstanding patterns of

marginalization. If anything, these images show how fears stoked by a

viral pandemic are especially amenable to being channeled through

longstanding systems of classification, purity, and stigma based on

caste, class, and occupation.

Migrants queue at Peetol checkpost on NH48 in Gujarat’s Dahod district, on the state’s border with Madhya Pradesh.

Clearly the pandemic

has produced certain specific responses, such as disturbing images of

migrants being rounded up and sprayed with harmful chemicals. Yet these

responses are hardly divorced from longstanding patterns of

marginalization. If anything, these images show how fears stoked by a

viral pandemic are especially amenable to being channeled through

longstanding systems of classification, purity, and stigma based on

caste, class, and occupation.Why is the response of the Indian State and society so radically different to the labour which migrates abroad to the one that migrates within India?

I am sure your readers can guess the answer here. Whether in times of crisis or normalcy, states respond to citizens who are economically powerful and politically organized. The striking difference in how we treat international and internal migrants is particularly apparent if we think of wealthy international diasporas, such as Indians residing in the United States. Survey data indicates Indian-Americans have higher median household incomes than any other major ethnic group, including non-Hispanic whites. These diasporas are celebrated for their accomplishments and remittances, and feted at events such as the Howdy Modi rally held recently in Houston. The power of these groups fueled significant efforts to expand their standing and political rights, including the establishment of new categories of citizenship (such as the Overseas Citizens of India). Migrants sitting atop a bus as they leave from Lucknow.

By contrast, I know of no systematic efforts to celebrate and

acknowledge the contributions of poor circular migrants. Further, there

have been no efforts to think through how to expand their political

rights in destination cities. Efforts to provide them with city-based

identification documents to help them secure rental properties, PDS

benefits, or redressal from mistreatment from urban employers are few

and mostly spearheaded by civil society organizations. Instead, city

authorities tend to view migrants through the lens of enforcement rather

than accommodation. Circular migrants experience considerable police

repression in the cities they work within. This attitude remains

apparent in the reports and images of police violence towards migrants

during this current crisis, and the language of enforcement that

pervades recent government orders. Take for example the move to convert

sports facilities into ‘temporary jails’ for those found outside during

the lockdown, many of whom are likely to be populations like circular

migrants without reliable access to permanent shelters.

Migrants sitting atop a bus as they leave from Lucknow.

By contrast, I know of no systematic efforts to celebrate and

acknowledge the contributions of poor circular migrants. Further, there

have been no efforts to think through how to expand their political

rights in destination cities. Efforts to provide them with city-based

identification documents to help them secure rental properties, PDS

benefits, or redressal from mistreatment from urban employers are few

and mostly spearheaded by civil society organizations. Instead, city

authorities tend to view migrants through the lens of enforcement rather

than accommodation. Circular migrants experience considerable police

repression in the cities they work within. This attitude remains

apparent in the reports and images of police violence towards migrants

during this current crisis, and the language of enforcement that

pervades recent government orders. Take for example the move to convert

sports facilities into ‘temporary jails’ for those found outside during

the lockdown, many of whom are likely to be populations like circular

migrants without reliable access to permanent shelters.